Extended chords from the major scale

We shall now revisit major scale to learn about intervals of a ninth, eleventh and thirteenth and chords with these intervals. We'll also look at "sus" chords, "sixth" chords, "add 6" and "add 9" chords.

You will learn about the group of intervals collectively known as ninths, elevenths and thirteenths. You will learn about the ninth, eleventh and thirteenth chords in major, and hence inherited by the modes of major. You will also learn the add 9 and add 6 chords, and the "sus" chords, where a 4 replaces a 3, or a 2 replaces a 3, and sixth chords, where a 6 is added to the triad or seventh chord.

Click any chord shape to interact (find other voicings, change root, or edit, or save to your favourites)

Intervals of a ninth, eleventh and thirteenth

An interval of an octave plus a second (14 semitones) is called a 9. An interval of an octave plus a b2 (13 semitones) is called a b9. An interval of an octave plus a #2 (14 semitones) is called a #9. Collectively these are known as ninths, and the b9 and #9 are known as altered ninths. We'll look at the #9 later. An interval of an octave plus a fourth (17 semitones) is called an eleventh (11). An interval of an octave plus a #4 (18 semitones) is called an #eleventh (#11). An interval of an octave plus a sixth (21 semitones) is called an thirteenth. An interval of an octave plus a b6 (20 semitones) is called an b13.

Pragmatically, these can be thought of as forming intervals of a b2, 2, #2, 4, #4, b6 and 6 with some octave of the chord root (especially when a bass player or pianist is providing the root in some low register). When soloing, this is also how we think of a landing pitch, for example 2 semitones above any member of the chord root’s pitch class (remember, a pitch class is all the Cs or all the Eb’s available on your instrument)

The logic of naming chords

More complex chords comprise adding intervals to less complex chords. Thus, a seventh chord adds a 7 or b7 to a triad, a ninth chord adds a b9, 9 or #9 to a seventh chord; an eleventh chord adds a 11 or #11 to a ninth chord; a thirteenth chord adds a 13 or b13 to an eleventh chord. Provided the chord has no altered fifths or ninths or elevenths, it is named very simply

· If the seventh chord is a m7, then all these others are m9, m11, m13

· If the seventh chord is a maj7, we get maj9, maj11 and maj13

· If the seventh chord is a dominant seventh, we get 9, 11, 13.

Sometimes, these higher intervals are added with "gaps", such as adding a 9 to a triad (there is a gap where the seventh interval is missing), or an eleventh or a thirteenth to a seventh chord. In these case, the base chord type is given, along with the added interval. Thus

· minor triad or major triad, with a ninth is named min add 9 or maj add 9. Or min / 9 and maj / 9.

· A seventh chord type plus an eleventh is named as seventh chord type add 11 or / 11. For example, 7 add 11, m7 add 11, m7b5 add 11.

· A seventh chord type plus a sixth (thirteenth) is named as seventh chord type add 6 or / 6. For example, 7 add 6, maj7 add 6.

· A ninth chord type plus a sixth (thirteenth) is named as ninth chord type add 6 or / 6. For example, 9 add 6, maj9 add 6

· A sixth chord type plus ninth is named as sixth chord type add 9. For example, 6 add 9 or -6 add 9.

A chord type whose third has been replaced by a fourth is named as chord type sus. So,

· 7 sus, 13 sus, or simply sus for a major or minor triad with a replaced third.

If we have alterations to the 9, 11 or 13, they are explicitly mentioned. An unaltered chord type is named, followed by the alterations (and additions) that affect it. We have already seen this with the m7b5 chord. The unaltered chord is m7. The alteration is to flatten its fifth. m7b9 means a m7 chord with the addition of a b9 ... we don't write m9b9. 7#9 means adding a #9 to a dominant 7. 7#9b5 means a dominant 7 chord with a flat five and a sharp nine. maj7b5 means we have a major 7 chord whose fifth has been flattened. maj7#11 means we have a maj7 chord with an additional #11.

The sixth chord and function

If we add an interval of a 6 (not b6) to a major or minor triad, we get a major or minor 6 chord ((maj) 6, min6 or m6 or -6). In major, I and V host major 6 chords, <1, 3, 5, 6>. II hosts a min6 chord <1, b3, 5, 6>. They work the same way as the triads off the same roots, in terms of drive. But V6 loses some of its drive, because its sixth is the third of the I triad, so it doesn't resolve to I ... it's there already. I6 is slightly less stable than Imaj. II-6 is more unstable than II- and II-7.

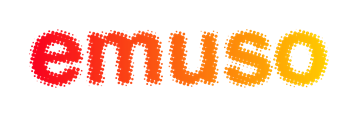

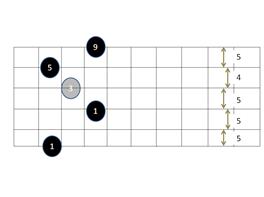

On guitar, a maj6 with all its intervals is quite hard to play, so we frequently omit the fifth. For example: .

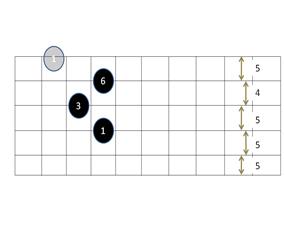

The -6 chord is easier to play. Here are a couple of voicings: <1, 6, b3u, 5u (, 1u2)> and <1, 5, 6, b3>. The former (left diagram) is frequently used a groove chord in its own right (dorian).

Note that <1, b3, 6, 1u> sounds like part of a dominant 7 rooted a fifth lower.

The minor7#5 chord and function

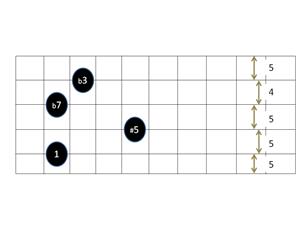

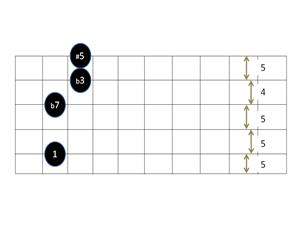

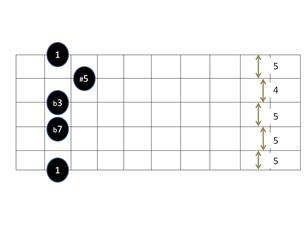

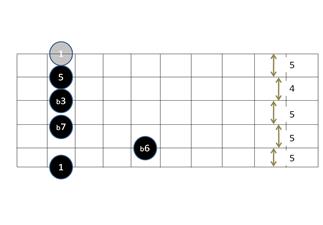

If

we replace the 5 by a #5 (b6) in III-7 and VI-7, we

get the -7#5

chords. If we add a b6 to III-7 and VI-7, we get

-7b6 which have a natural

fifth and a flat 6 also. The -7#5 and -7b6 chords are great

sounding chord when voiced right. These III and VI chords act as stable chords

and substitutes for Imaj. Here are some voicings:

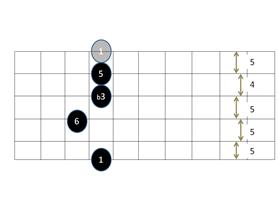

-7#5: <1, #5, b7,b3u> (top left) , <1, b7,b3u, #5u> (top right), <1, b7, b3u, #5u, 1u2> (bottom)

-7b6: <1, b6, b7,b3u, 5u, (1u2)>

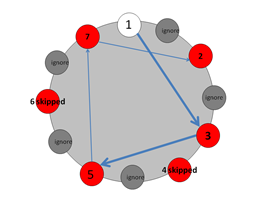

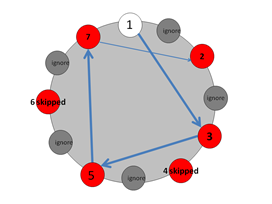

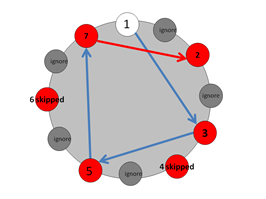

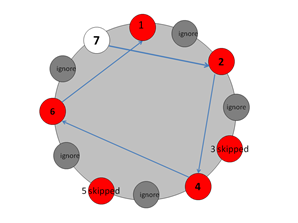

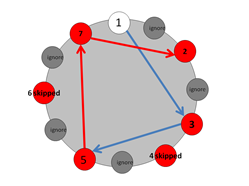

Here are triads again (three chosen notes ... top left clock), and sevenths again (four chosen notes ... top right clock). Ninths are the next extension (five chosen notes ... red arrow bottom clock). These clocks shows the choose-skip rule applied to 1 of major. 2 gets skipped initially (as the triad part of the ninth is chosen), but it gets chosen in the next octave.

Visually the ninth is always the upper scale neighbour (clockwise) to the root of the chord (look at 2 and 1 in the clock above). If they are separated by one note (as in this example), the interval is 9. If they appear next to each other, the interval is a b9. Building a ninth off 3 or 7, using the choose skip rule, shows the b9 (next clocks).

The resultant chords, collectively known as ninths, contain some sort of seventh chord, and a 9 or b9 from the root. Visually, we see that only VII and III have b9's in their ninth chords. All the rest have 9s. Here are the chord names. Spoken, they are "major nine", "minor nine", "minor seven flat nine", "dominant nine" (symbol 9 by itself), and "minor seven flat nine flat five".

|

Key location |

Triad |

Seventh (triad + seventh interval) |

Ninth (7th chord + 9th interval) |

|

I |

maj <1, 3, 5> |

maj7 (maj + 7) |

maj9 (maj7 + 9) |

|

II |

min <1, b3, 5> |

m7 (min + b7) |

m9 (m7 + 9) |

|

III |

min <1, b3, 5> |

m7 (min + b7) |

m7b9 (m7 + b9) |

|

IV |

maj <1, 3, 5> |

maj7 (maj + 7) |

maj9 (maj7 + 9) |

|

V |

maj <1, 3, 5> |

7 (maj + b7) |

9 (7 + 9) |

|

VI |

min <1, b3, 5> |

m7 (min + b7) |

m9 (m7 + 9) |

|

VII |

dim <1, b3, b5> |

m7b5 (dim + b7) |

m7b9b5 (m7b5 + b9) |

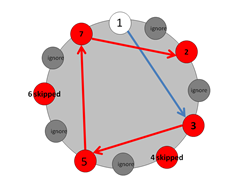

There are two other ways to think about ninth chords. They can be seen (left clock) as two triads stacked on top of each other ... the 5 of the lower triad (blue arrows) is the root of the upper triad (red arrows). Or they can be seen (right clock ) as the lower triad, with a seventh chord (red arrows) stacked on its third.

Similarly, a seventh chord can be thought of as a root, and an upper triad stacked off the third of the seventh.

Add 9 chords and function

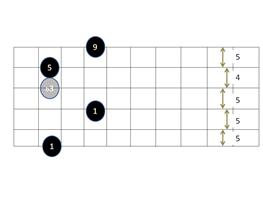

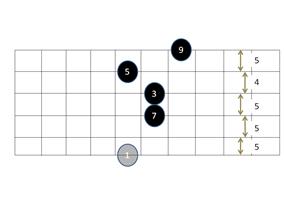

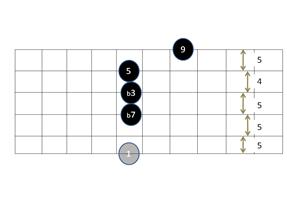

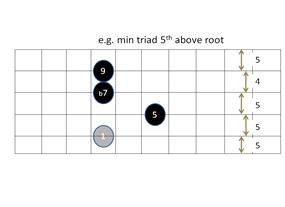

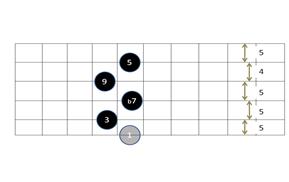

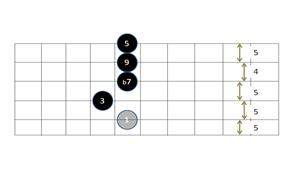

Sometimes a ninth gets added to a major or minor triad, rather than on top of a seventh chord. In which case, we have a I, IV and V major add9 <1, 3, 5, 9> (left diagram) or II, VI minor add9 <1, b3, 5, 9> (right diagram) chords. Their symbols are add 9 or /9, and m add 9 or m /9. By omitting the third, an ambiguous chord is created, used in rock.

Chord voicings for ninths

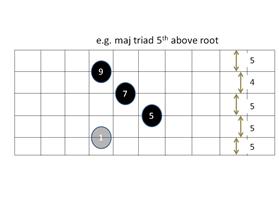

Five note chord voicings often omit the root or unaltered fifth (not both) of the ninth chord as inessential to the sound. If the chord has an altered fifth, the root can still be omitted. Modern piano chord voicings often drop the ninth by an octave, resulting in an interval of three semitones (#2, aka b3), two semitones (2) and 1 semitone (b2) above the root. Then things get blurry with chord naming. Most still name such voicings as ninths. So, know what a 9 or b9 is, but don't restrict yourself to always playing this in the next octave above the chord root. However, b9 and #9 are normally voiced above the third. For example, <1, 3, b7, #9> is a great voicing for a 7#9 chord (discussed shortly), whereas <1, #2, 3, b7> is unusual (not to mention virtually impossible to finger on a guitar, yet easy on a piano). The same comment applies when improvising. Look at the left clock above ... if the third of the lower triad is omitted, then you have just the upper triad positioned a fifth above the root. This is a beautiful sounding voicing, and somewhat less stable, since its missing one of the key's stable tones. So, you can play V triad over I, VI- triad over II, I triad over IV, II- triad over V, III- triad over VI, IV triad over VII. I is optional in following voicings.

Their use really depends on the genre of music. It is common to use triads and sevenths in the harmony, with the major 9 interval appearing in the melody. Any kind of ninth in chord progressions are rare in pop and ballads, and pretty much never occur in country-and-western and folk. Where they do occur, its mostly as variations of the stable and medium drive chords, and not so much as a high drive chord. They almost never occur in Rock, with one main exception, the 7#9 chord, favoured by Jimi Hendrix, but we'll discuss that later. As a standalone chord sound, the maj9 and m9 chords are popular in Jazz and Funk, when a groove is set up on that chord, perhaps followed by a change to another tonal centre with the same chord type. The dominant 9 chord is used a lot in Blues and Funk as well, in a similar way. A b9 (b2) above the chord root creates a very clashy sound, so the m7b9 chord and m7b9b5 chords are pretty much never used. Hence these are omitted in the table below. Stability-wise, a ninth chord ranks about the same as the seventh chord that makes up its lower four notes. For major key, this gives us the following rankings ordered by stability (and including the triads). The most unstable is at the top.

|

High Drive |

VII -7b5 VII dim V9 V7 Vmaj Vmaj / 9 |

|

Medium Drive |

II- II-9 II- / 9 II-7 IVmaj IV maj9 IVmaj / 9 IV maj7 |

|

Stable |

III-7 III- VI- VI- / 9 VI-9 I maj9, Imaj / 9 I maj7 Imaj |

Eleventh chords, sus chords

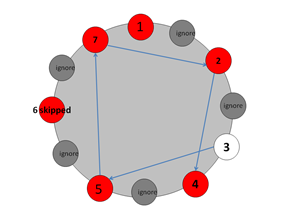

These are the next extension beyond ninths, found by applying the choose-skip rule from each key location to select six notes... Each key location, apart from IV, has intervals of an 11 to the sixth selected note in the chord built from there. IV's chord has an interval of a #11. When present, #11 is usually voiced above the fifth. Visually, the eleventh appears next to (above) the third of the chord. If there is no intervening note, visually, we have an 11. Otherwise, we have a #11. If the chord has no fifth present, then #11 is named as b5.

It's useful to think of 11 and 4 interchangeably. Often, with re-voicing, the 4 may be present in the same octave as the root, or it may be in the next octave. I wouldn't be too pedantic about this.

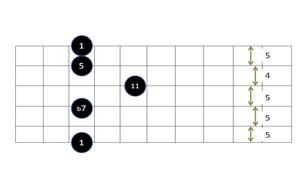

Name-wise, if we have the essential components of a ninth chord present, then with an eleventh as well, we name the chord as some sort of eleventh. Otherwise, we name the chord as some sort of sus 4 or add 11. For example <1, 3, (5 ... inessential), b7, 9, 11> is a dominant 11 (11), whereas <1, 3, 5, b7, 11> is a dominant 7 add 11 (7 add 11 or 7 / 11), while <1, 4, 5, b7> is a 7 sus 4 or simply 7 sus.

I hosts a major eleventh (maj11) chord <1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 11>. This is almost never used because the 11 clashes with the 3 of Imaj. We can ignore III and VII as their ninth chords aren't used, and likewise, nor are their elevenths. II and VI create a minor eleventh (m11, -11) chord <1, b3, 5, b7, 9, 11> which does sound good (the b3 and the 11 do not clash). V creates a dominant eleventh (11) chord <1, 3, 5, b7, 9, 11>. Again, the 3 clashes with 11, though this quite a cool sound because of the b7 being present as well.

To avoid these clashes, we can omit the 3, and replace it by the 11 (4). This is known as a suspension. Originally, this came about from holding the 4 melodically from one bar (say, over IV chord) into the beginning of the next bar whose chord is (nearly) a I major triad, and then replacing the 4 by 3 to create the full I major triad. <1, 4, 5> is known as a sus4 chord.

For example: IV<1, 5, 1u, 3u> | I sus4 <1, 5, 1u, 4u> | I<1, 5, 1u, 3u>

Another form of sus chord is the sus2 <1, 2, 5>, where the 3 has been replaced by 2, analogous to the above.

For example: V7<1d, b7d, 3, 5> | Isus2 <1, 5, 1u, 2u> | I<1, 5, 1u, 3u>

Eleventh chord voicings

The root and the fifth (both) can be omitted as inessential to the sound. But if the fifth is altered, it must be present. The third is often omitted. I've use 2u instead of 9, and 4u instead of 11, just to highlight the fact these are located in the next octave above the root. Here are a few examples:

V7sus4: <1, b7, 4u, 5u, 1u2>

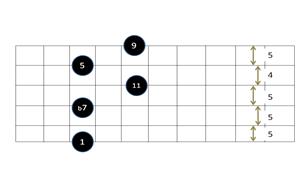

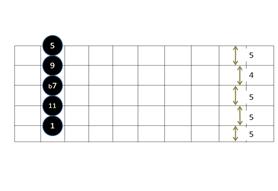

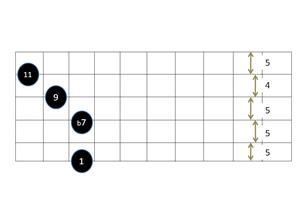

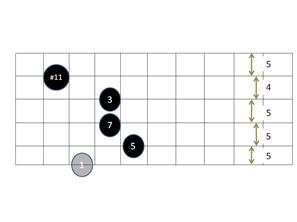

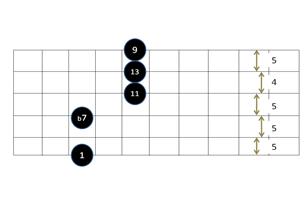

V11: <1, b7, 4u, 5u, 2u2> (left), <1, 4, b7, 2u, 5u> (right), <1, b7, 2u, 4u> (bottom)

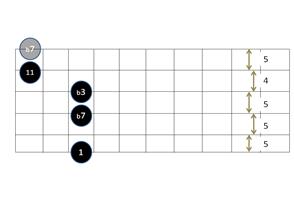

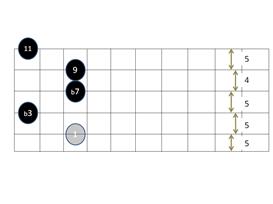

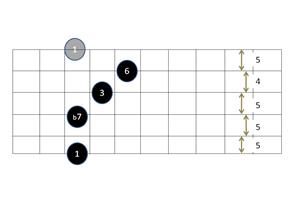

II-11, VI-11: <1, b7, b3u, 4u, b7u> (left) <1, b3, b7, 2u, 4u> (right)

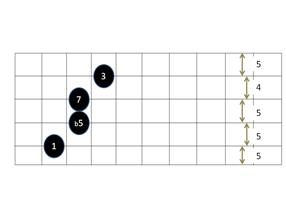

IVmaj7#11: <1, 5, 7, 3, #4u> IVmaj7b5: <1, b5, 7, 3u>

Thirteenth chords and add 6 chords

Our last category of chords adds a seventh note, which is 13th (6) above the root of the chord, using the choose-skip rule. Again, both the root and unaltered fifth can be omitted as inessential to the sound. Chords hosted off I, II, IV, V have a 6 or 13. III, VI and VII have a b6 or b13. These fall in the same drive categories as their seventh chords, for how they are used. This gives us I and IV maj9 add 6 <1, 3, 5, 6, 7, 9>, V13 <1, 3, 5, b7, 9, 11, 13> and V7add6 <1, 3, 5, 6, b7>. II, III, VI and VII thirteenths aren't used. Here are a few voicings...

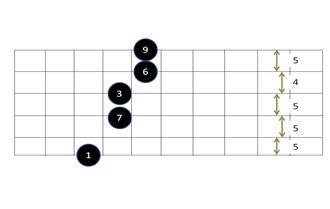

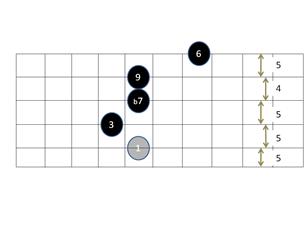

I, IV maj9 add6: <1, 7, 3u, 6u, 2u>

V13: <1, b7, 4u, 6u, 2u2> V7 add6: <1, b7, 3u, 6u, 1u2>

V9 add 6: <1, 3, b7, 2u, 6u>

We've learned about the intervals of b9, 9, and #9, along with #11, and 13 and b13. We've looked at how ninth, eleventh and thirteenth chord are built from the major scale. We've seen that five note chords (ninths) can omit the root or the fifth (provided it's not altered), and that six and seventh note chords can omit both the root and the fifth (provided it's not altered). In terms of where these intervals are actually voiced, there is a lot of flexibility, except that altered ninth intervals normal appear about the third. We've also seen sixth chords, where a 6 gets added to triads and seventh chords. We've seen sus chords, where the 3 is replaced by the 4 or the 2. We've looked at chord function also ... these more complex chords essentially slot into the same categories as their seventh chords.